The changing nature of selling out

>text: Michael Raine

As times change, so do our ethics. Nowhere in the music industry has this become more apparent than in the long-running debate over “selling out.”

It used to be so simple. From the 1960s to the early ‘90s, the consensus among those concerned with the artistic merit was, if a band or songwriter ad-licenced their song they were a sell out, worthy of all the scorn The Village Voice could muster. In the 2000s, that train of thought is all but extinct.

Licencing music has become an accepted practice, with even The Village Voice asking in 2010, “Is It Possible to Sell Out?” After all, when beacons of artistic integrity, from Bob Dylan to Kurt Vile, are ad-licencing their songs, it does appear that the concept of “selling out” is a cultural relic, a symbol of a past generations’ ill-advised attempts at rebelling – like the trendy Chairman Mao pin.

A similar argument was made by author Hua Hsu on Grantland.com in his article “M.I.A. and Impossibility of Selling Out.”

However, isn’t selling out always possible as long as artists have moral and ethical beliefs? Selling out shouldn’t be a black and white, yes/no, issue but in the new age of music and advertising, selling out is harder to identify than it used to be.

In 1971, the average American was exposed to a little more than 550 advertisements per day, according to author David Shenk. The best estimates indicate that the average American is currently exposed to anywhere from 1,500 to over 3,000 ads daily. In 1971, college radio and alternative rock stations in urban centres were the primary source of new music for anyone in the counter culture.

In the last two years, well established and long running alternative rock stations have changed formats – to talk, gospel, or top-40 – in Orlando, New York City, Chicago, and Philadelphia, and a number of college radio stations have also been sold off.

With this new reality, no one can blame artists for ad-licencing their music. It’s become an accepted fact that advertisements provide much needed money and exposure for indie bands who would otherwise have very little of either.

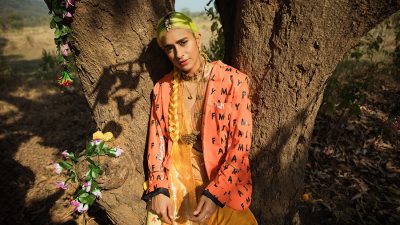

You can credit/blame Moby for discovering the formula. His 1999 album “Play” was the most licenced album of all time, with all 18 tracks being used in a TV show, movie, or commercial, and in some instances all three. As his manager Eric Härler explained, they simply needed exposure because radio stations refused to play Moby’s music.

Getting exposure through ads worked better than anyone could’ve imagined, as “Play” became the best-selling techno album of all time and transformed Moby from cult DJ to global star. At the time Moby took a lot of flak of from fans and the music press for being a sell out. One fan even went so far as to sell Moby’s soul on eBay (Moby’s “soul” was an empty jar but you get his point).

It’s an argument that seems antiquated 13 years later, when we barely notice Civic using a Vampire Weekend song to sell cars. Derek Miller, song writer and one half of the indie duo Sleigh Bells, summed up it best while discussing his

own band’s decision to licence the song “Rhythm Riot” for use in Honda’s commercial for a hybrid SUV. “The ‘sell out’ discussion never even happened, we happily license our music for movies and advertisements on a case-by-case basis,” Miller told the Boston edition of Metro newspaper. “It’s almost pretentious to avoid the opportunity, especially in this climate.”

It’s the “case-by-case basis” part of Miller’s statement that best explains the modern dilemma over selling out. What if, for example, Moby, a committed vegan and vocal supporter of PETA, had licenced his music to KFC (I’d suggest using “Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad” to sell the Double Down)? Would that be selling out? The simple answer is yes.

That’s why when The Village Voices’ Zach Baron writes, “selling out has long since stopped existing as a meaningful concept,” he’s only partially right. He is right that selling out isn’t an all-encompassing fear for indie bands the way it used to be. But selling out is still possible and is still meaningful.

If a fervent anti-war band like Rage Against the Machine ad-licenced a song to war profiteer Halliburton, that would undoubtedly compromise their integrity. However, the same couldn’t be said for flag-waving, pro-war, country singer Toby Keith.

In essence, the debate over selling out should be less intellectually lazy than has often been the case. In the 2000s, saying “yes” to every company that comes knocking makes no more sense than saying “no” did in the 1990s.

Just because a bands’ views over right and wrong have changed – from the ‘60s-style “all capitalism is bad” to a more 2000s viewpoint of “I love me some Heinz ketchup but Hummer is a gas-sucking parasite” – doesn’t mean ethics don’t exist. And as long as they do exist, it is still possible to sell out.

Photo of Moby by Katy Baugh