Self-Mythology: what Lana Del Rey & Rick Ross learned from Bob Dylan

test: Michael Raine

I have a confession to make. I do not find current rock and roll interesting. In fact, YouTube sensations, top-40 pop princesses, and bling-clad rap stars are far more interesting than any current rock and roll act. That is not to say, however, that I don’t enjoy listening to new rock and roll (for purposes of brevity I’m using “rock and roll” as a catch-all term for any guitar-driven, folk/blues/rock-based band or artist). But there is a difference between enjoying listening to music and finding the person(s) who make that music interesting. On the other side, I rarely listen to rap and listen even less top-40 pop, but I do find many pop and rap stars interesting. The reason: seemingly worried about being labeled a liar or, even worse, inauthentic, rock and roll acts have ceded the genre’s tradition of self-mythology to others.

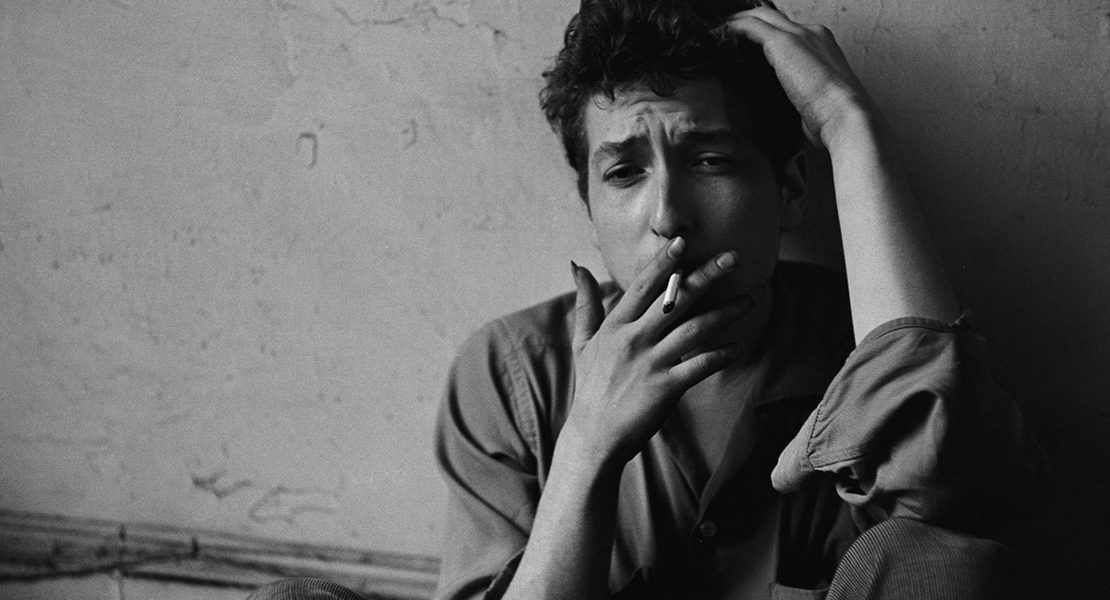

“He is a complicated young man, surrounded now by complicated rumors,” wrote Newsweek magazine’s Andrea Svedburg in a 1963 expose that blew the lid on Bob Dylan’s carefully constructed self-mythology. Dylan himself worried the article might ruin his career. What would his fans think when they found out he wasn’t an orphan who rode the rails, honing his musical skills alongside hobos and troubadours? Or that he never played in Bobby Vee’s band and was never in the circus? Would fans stop buying albums and protesters stop singing Blowin’ in the Wind when they found out their idol – a symbol of authenticity and the hesitant voice of a generation – was really Robert Zimmerman, a middle class Jew with two loving parents from Hibbing, Minnesota? Yes, fans cared and some even felt betrayed. But while fans and critics debated the meaning of Dylan’s truth, the man at the centre of the debate did nothing. He didn’t acknowledge the truth and didn’t apologize for it. He just went on playing the character he’d constructed until it was time to tryout a new character. By not acknowledging the truth Dylan allowed the debate over authenticity serve a larger purpose. The debate became fuel for the myth of Bob Dylan.

Dylan was not the first or last musician partake in the art of self-mythology. Robert Johnson was an unknown and unexceptional guitar player, the myth goes, until he had a midnight meeting with the Devil. At a crossroads in Clarksdale, Mississippi in the early-1930s, Johnson sold his soul for the ability to be the greatest blues player in history. There is some debate as to whether or not Johnson constructed the myth himself, but it continues to live on as one of the greatest myths in music history. Most artists don’t go to such lengths in their myth-making as to invoke the devil, but many – such as Kurt Cobain, who claimed he was homeless and lived under a bridge as a teenager – have told white lies and/or significantly revised the truth in order to craft an image. Many icons, from Jim Morrison and David Bowie to Morrissey and Will Oldham, understood the benefits for themselves and the fans that a little self-mythology can bring.

Unfortunately, self-mythology is a dying art – at least in rock and roll – and it’s dying for two reasons. One, in the age of the Internet, the paparazzi, and TMZ, public figures cannot hide details of their past for even a short period of time. This does leaves little room for fabrication, and most artists do not subscribe to the misconception that they can get away with it. Two, the desire to mythologize has been trumped by notions of authenticity and the belief that musicians should somehow be like their audience.

Currently, there are many good bands and songwriters but there are very few interesting characters. Interesting characters are what make people a fan of the band, rather than just a fan of the songs. After all, the music alone is enough to make someone listen to a band but it takes a look, an attitude, and a story to make someone love the band. This lesson may have been forgotten by most of the rock and roll scene but it hasn’t been forgotten completely.

October 2011: the song ‘Video Games’ appears online, complete with a David Lynch-inspired, retro cool video. The song goes viral overnight and the world is introduced to Lana Del Rey, a 20-something girl from a New Jersey trailer park with a soothing voice, big hair, bigger lips and a love of both hip-hop style and classic Hollywood. It’s appears to be the perfect Cinderella story. She is pronounced the “Next Big Thing” at the Q Awards and every music magazine rushes to claim her as their own.

Just as quickly the facade comes crashing down when a blog, Hipster Runoff, reveals that Del Rey is really Lizzy Grant; failed major label pop singer and daughter of a millionaire domain investor from Lake Placid, New York. Of course, countless debates over authenticity erupt, and the controversy only assures that her debut album, Born to Die, rockets to the top of the charts. Next month’s issue of GQ magazine’s British edition names Del Rey “Woman of the Year”.

In 2008 rapper Rick Ross already had to two number one albums to his name. He’d successfully built an image as a narco-kingpin, claiming he had been selling drugs since he was 13, “got rich off cocaine” before he had recorded a single verse, and dropped hints that he had links to notorious drug lord Pablo Escobar, and former Panamanian ruler Manuel Noriega. It all served to build his self-mythology.

And what happened when it was revealed that Rick Ross was actually William Roberts, former corrections officer? Nothing, he just kept playing the character, not conceding anything, and fans kept buying in. His next three albums went straight to the top of the Billboard charts. As Rolling Stone magazine writer Josh Eells put it, “Ross is like a hip-hop Gatsby, who, by pronouncing himself a kingpin, basically became one.”

Lana Del Rey and Rick Ross are proof that self-mythology can still work. No one can keep the myth going forever – and no one ever could, as Dylan proved – but that’s not the point. Self-mythology has always been about creating an image that is more interesting than the truth while knowing fans will believe what they want to believe. After all, the truth more often than not is boring, certainly more boring than the myth. So who wouldn’t want to buy into the myth? And the boring truth, once is it inevitably unearthed, is made more interesting by the mere existence of the myth. That has always been the real long-term benefit of self-mythology. The goal is not to trick people forever, but just long enough that finding out the boring truth becomes interesting.

The absence of myths in rock and roll is unfortunate development for anyone who is interested not just in the music but in the story. Those super fans and music nerds who read rock star biographies, spend hours poring over music magazines, watching documentaries, and scouring liner notes for interesting tidbits of information. Myths made the mundane interesting. But the torch has been passed. Self-mythology is no longer the domain of rock and roll stars. Pop and rap stars are its new practitioners and that is the main reason why I would rather listen to an album by The Shins, but would rather read about Rick Ross.