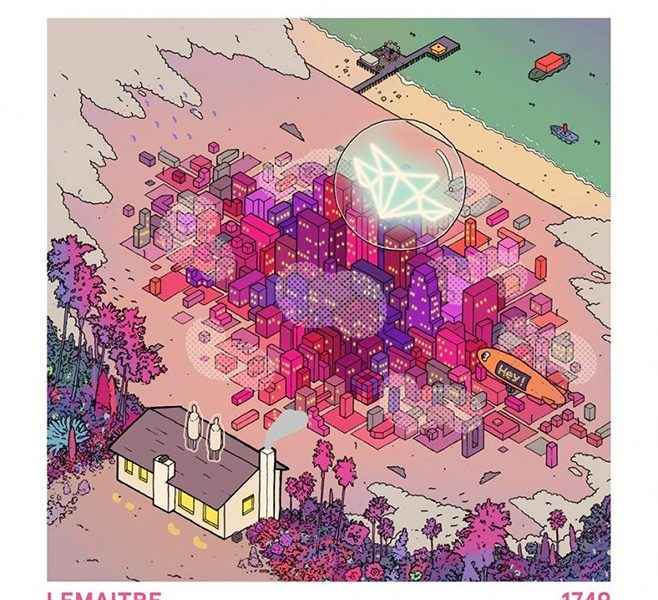

Stasis, violence, and Lemaitre’s “1749” EP

by Scott Wilson

Revolution is not a term that should be tossed about like a plastic toy football in the lexicon of modern democratic society. However, one would need to be exceptionally tone-deaf to not notice the rising dissatisfaction among international popular culture.

In Ukraine, Spain, and Arab countries, protests erupt with previously unheard of regularity. In the United States, people are using forbidden words like ‘socialism’ and ‘guaranteed human rights’ with a level of reckless abandon that hasn’t been heard in sixty years. And in art, fresh ways of thinking combined with new technologies and the ever-creating nature of youth has brought about a new golden age.

In music, specifically, we’ve seen the birth of more styles and movements in the past ten years than in the previous hundred before. We are living in a period of unmitigated innovation, where outdated ways are replaced like so many gas-guzzling SUVs have been replaced with hybrids.

In some circles, at least, things are changing. In others, not so much. Change isn’t always good, nor is it by definition bad. It’s just different. It is Yin. Yang, then, is sameness, perfection, repetition, also neither good nor bad. It’s in the second category that Lemaitre’s 1749 fits.

On the first listen, 1749 (named after the address where the five-track EP was recorded) brings to mind thoughts like, “Where have I heard this before?” Lemaitre has links to bands like fun., Phoenix, Moby, and a million lesser house-musicians in the way that early Bob Dylan does with decades-old New England folk. It’s basically the same in terms of instruments, hooks, breaks, tone, etc., but the individual artist(s) add their own flourish.

In this way, working off the lessons and triumphs of musicians who came before, a hit can be made by reduction. That is, through boiling away the unpopular riffs and movements that have stymied the careers of others, and focusing on the sounds that have proven to attract positive attention, 1749 represents the pinnacle of pop-electronic music. Not a note is out of place, not a single sound is uncalled for. It is the very definition of hard work and attention to detail.

In this plush bed of compliments, with its down comforter of allusions to some of the radio’s greatest contributors, lies a cold toenail clipping of criticism.

1749 is in no way a rebel anthem; nothing about it is pushing the limits of music in any firm direction. This EP is a collection of five pretty good songs that can be played at low to medium volume on top-40 radio or on the PA systems of stores in the mall, without objection by anybody inclined to listen to those music sources.

Yet, a defense of Lemaitre’s traditionalism can be made from a statement Morrissey presents in his autobiography. He says that whenever his managers gave Rolling Stone an opportunity to review a Smiths album, “[the] magazine repeatedly said ‘No, thanks,’ and have kept their word for thirty years, yet they will applaud any sub-Smiths progeny who taps on their bunker. But that’s life. Go first and be sure of a hard time.”

Art is a difficult and risky endeavor, even when you are as talented as the Lemaitre duo and their fantastic cast of featured singers. Morrissey’s vaulted status notwithstanding, originators rarely get the credit they deserve, and to ask a band to forget the artistic mastery they’ve worked so long and hard to achieve in search of an undefined “new” is a lot like asking the king of France to step down and let the mass of unwashed humanity decide how the country should be run.

Revolutions, be they in art or life, can be messy, risky, and – in the case of France – lead to the tyrannical rise of Napoleon Bonaparte and the dreary neoclassical art movement, but they can also improve the human condition.

The quality of Lemaitre’s 1749 isn’t a question of how good the music is, because it’s great, but whether the listener is satisfied with the status quo.